Actress Angelina Jolie has been forthcoming about her decision to respond proactively to the disease that took her mother, grandmother and aunt, sharing her reasons for choosing an elective mastectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) in editorials that appeared in The New York Times. While her candor is commendable, her public commentary has left many women with unanswered questions about the inherited forms of breast and ovarian cancers.

To ensure you’re prepared to respond to this “Angelina Jolie effect,” we asked UVA certified genetic counselor Martha Thomas, MS, to provide the facts on inherited forms of these cancers and clear up some misconceptions about the BRCA gene.

What is BRCA?

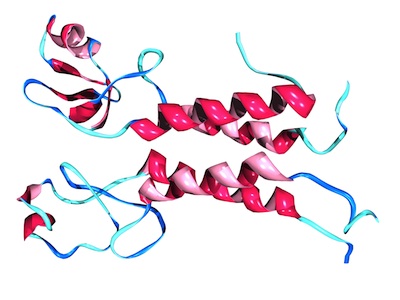

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are tumor suppressor genes found in all of us — both males and females. They have proteins that actually protect us against developing cancer by initiating apoptosis in abnormal cells, so we want these genes. They are doing good things.

What does it mean to be BRCA-positive?

Despite common misconceptions, if a patient is BRCA positive, it does not mean that they have the gene — we all have the gene. A BRCA-positive diagnosis means that there is a change or mutation in the BRCA gene’s DNA that is causing the gene to function improperly. If a patient is BRCA negative, then they are negative for any deleterious mutation that would cause the gene to stop doing its job.

What is the difference between BRCA1 and BRCA2?

We’re still learning about the differences between the genes; however, it has been shown that they are associated with different types of cancer. BRCA1 is most often linked to ovarian cancer and more aggressive forms of breast cancer — specifically, triple negative breast cancer. Mutations in BRCA2 still increase a patient’s risk for breast and/or ovarian cancers, however there are other cancer risks as well, including pancreatic, esophageal and prostate cancer, as well as melanoma.

If a patient tests positive for a BRCA mutation, what are her risks for developing cancer?

Historically, if a patient tests positive for BRCA1, she has an 87 percent chance of developing breast cancer in her lifetime. In contrast, women who are BRCA negative have a 12 percent chance of having the disease. A woman’s risk of developing ovarian cancer is 54 percent if she tests positive for the BRCA1 mutation; the risk is less than 2 percent for those without the mutation. As genetic testing becomes more widespread among those with and without a family history of cancer, these statistics are continually changing.

Remind your patients that just because they do not have the BRCA gene mutation does not mean they will not get cancer. Ninety to 95 percent of breast cancers are sporadic (not inherited) and 80 percent of ovarian cancers are sporadic.

Who should be screened for BRCA?

A BRCA mutation is very rare, impacting less than 1 percent of people in the general population. However, because genetic testing can lead to early detection and improved outcomes, it’s important to identify those patients who may benefit from BRCA screening.

The U.S. Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF) has comprehensive guidelines for selecting patients eligible for BRCA genetic testing. Keep in mind that these are suggested guidelines and are not absolute. Some of the key characteristics of those eligible for BRCA testing, according to the USPSTF, include:

- A personal history of cancer, especially those diagnosed as having breast cancer under age 50 or with ovarian cancer at any age

- A family history of breast, ovarian or pancreatic cancer, including maternal and paternal relatives

- A family member who tested positive for the BRCA mutation

- Women of Ashkenazi Jewish descent

Any woman with a strong family history of cancer should receive genetic counseling, which provides her with a risk assessment and information about the options available for genetic testing.

What treatment options are available to those women who are BRCA-positive?

There are two primary options available to women who are BRCA-positive. One is increased surveillance, which does not decrease a woman’s risk of getting cancer but it does help improve the chances that the cancer will be found at an earlier stage when it is more easily treated. Surveillance may include regular mammograms, as well as more advanced imaging like MRI and tomosynthesis.

The other option is risk reduction, which may include medications like tamoxifen or surgery. In premenopausal women, removing the ovaries reduces a woman’s risk for both breast and ovarian cancer. Of course there is the option of doing nothing, but it’s not recommended.

Why should a patient be referred to a UVA genetic counselor?

BRCA is the most well-known gene associated with cancer, but there are many others. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations are linked to 40 percent of hereditary breast cancers, so in actuality, the majority of hereditary breast cancers are caused by mutations in non-BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes. The tests that I send out cover the full spectrum of potential mutations, so that we get all of the information we need the first time around. This is important because often insurance won’t pay for multiple tests. If a test comes back negative for BRCA and we want to test for other genes, then the patient may end up paying.

Our team of genetic counselors has experience with these large-panel tests, so we can interpret the results and translate them into clinical recommendations, which can often be a challenge. I have a full hour with patients to counsel them on their test results and, as an added benefit, I handle all of the insurance billing and any snafus that arise. UVA genetic counselors are always available to step in at any phase of a patient evaluation and will work with referring physicians to ensure patients are well informed of their options for testing and the recommended approach to treatment.

For more information about genetic testing at UVA or to speak with Martha Thomas, contact her assistant, Sheryl Green, at 434.982.1004.